As you hike the base trail from the parking lot to Taughannock Falls, take a close look around. Everything you see, from the towering cliff walls to the birds flitting from rim to rim, tells a story.

Made in the Shade

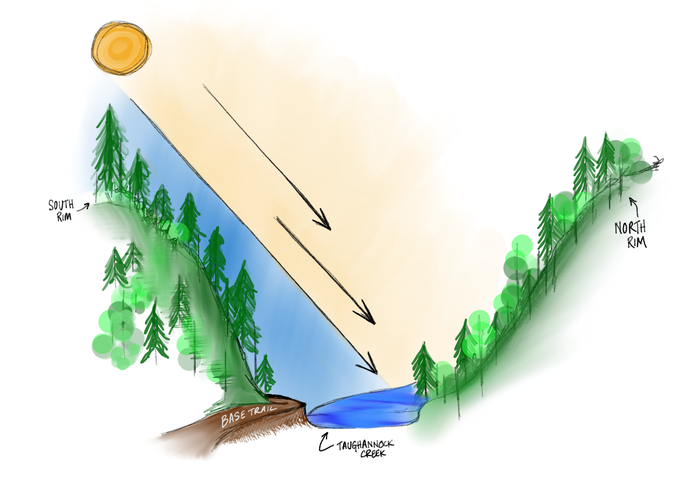

The gorge is well-treed, but how do the trees on one side of the gorge compare to the other side? On the base trail side, you'll see mostly eastern hemlock (evergreen) trees. On the northern slopes across the stream bed, the trees are deciduous, mostly maple and oak. Why the difference? Microclimates!

Illustration by Scott Dawson. Adapted from park signage.

The northern side of the gorge receives more direct sunlight, creating a different microclimate. The differences in temperature, sun exposure, soil condition and the slope determine what plants will thrive in a specific location. The hemlock trees have dark foliage, helping them absorb light in shady conditions. Their root system allows them to live on steep slopes, too, which is why you find them thriving in gorges.

Since we're above the equator, the sun is always in the southern half of the sky. This means the southern side of the gorge is continually in shadow, making it cool and moist. The northern side of the gorge gets that abundant sunshine, making it warm and dry. Up on the rim trail, sunlight is evenly distributed, resulting in drier conditions and less specialization of types of trees.

Clinging for Dear Life

High on the cliff walls, you can see evergreens clinging to the rock walls. These are red cedars, and the climate they're in is not unlike a desert canyon wall. The south-facing walls are in frequent sunlight, keeping them quite dry. Cedars are drought-resistant and love the sun.

Contrast this harsh environment with the base trail itself, which is mostly shaded and moist. The stands of sugar maples, black and yellow birches thrive in the rich, wet soil.

Taking Flight

Look up as you hike around the park. There are plenty of ducks and birds to look at! One of my favorite sights is of ducks taking flight from the upper areas of the creek, skimming the surface as they search for another place to land. Higher in the air, and depending very much on the time of day, you can see brown bats, pigeons and swallows. The high gorge walls provide them with a (relatively) safe refuge from predators. Speaking of predators, you may be lucky to spot several turkey vultures flying about, too. These are huge birds, and when you're hiking the rim and they take flight from a nearby roost, you'll definitely take notice.

Peregrine falcons call the park home, too, and they were photographed as early as 1926 in the park. The species disappeared from the area in the mid-1960s due to the use of DDT, and in 1970 they were placed on the Endangered Species list. On one of the park's placards, you can read about an attempt by Cornell scientists to re-introduce the peregrine falcon to the park in 1975:

They placed three young, captive-bred falcons in a "hack box" high on the cliffs across the stream. They were fed from a pipe from above until they were ready to be released. After the birds were freed, their movements were tracked with small radio transmitters. They didn't last long: scientists found two of the radio transmitters inside owl pellets, which are dry masses of regurgitated indigestible material. A great horned owl, the largest of its kind in our woods, had eaten two falcons. Scientists captured the third falcon before it could suffer the same fate. Intensive falcon release programs have been more successful elsewhere, and the peregrine falcon was removed from the Endangered Species list in 1999.

There's fantastic recent developments here, too: the peregrine returned to the park in 2020.

If you're a fan of bird cams, by the way, you'll love the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Live Cams site. The red-tailed hawks are amazing.